VIII. THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT

In recent decades, air quality control in Europe has led to a significant decrease of emissions and concentrations of pollutants in the atmosphere. Many pollutants exceed their ambient limits only in exceptional cases, yet a considerable part of the European population and ecosystems is still exposed to concentrations of pollutants that are greater than their legally set limits and values recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO Air Quality Guidelines). Air pollution in Europe is one of the most hazardous environmental factors. It is causing premature deaths, increasing the prevalence of a wide spectrum of diseases, and damaging vegetation and whole ecosystems, leading to loss of biological diversity. All this also brings considerable economic losses. Further improvements will require new measures and collaboration on global, continental, national and local levels, in most fields of the economy, and with public participation. Measures for improving air quality must include technological advancements, structural changes, including the optimization of infrastructure and regional planning, and changes of behaviour. Protection of natural capital and support for economic prosperity, human welfare and social development are components of the EU Roadmap 2050, which has been outlined by the 7th Environment Action Programme (EU 2013).

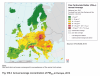

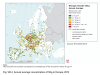

Emissions of main air pollutants have decreased in Europe since 1990. However, sufficient decreases have not been achieved in all sectors; emissions of certain pollutants even increased. For example, there has not been a sufficient decrease of emissions of NOx from mobile sources, which is the reason why ambient limits are not met in many towns and cities. During the last decade, emissions PM2.5 and benzo[a]pyrene from the burning of coal and bio- mass in households as well as in private and public buildings also increased in the EU. In the EU, these sources currently contribute the most to emissions of particles and benzo[a]pyrene (Fig. VIII.1).

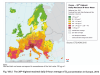

From the perspective of damage to human health, the most problematic are the current concentrations of particulate matter (PM) and ground-level ozone (O3), followed by benzo[a]pyrene and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). As far as damage to ecosystems is concerned, the most harmful pollutants are ground-level ozone (O3), ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). Polluted air causes serious health problems especially to inhabitants of towns and cities. The greatest damage to ecosystems is inflicted by O3, ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). It has been estimated that in EU member states, over the three-year period of 2011–2013, 17–30 % of urban inhabitants were exposed to limit-exceeding 24-hour concentrations of PM10, 9–14 % to over-limit annual concentrations of PM2.5, 25–28 % to over-limit annual concentrations of benzo[a]pyrene, 14–15 % to concentrations of O3 greater than the target value and 8–12 % to over-limit annual concentrations of NO2. The estimated percentage of the population exposed to concentrations exceeding WHO guideline values was even greater, e.g. by 87–93 % for PM2.5, by 85–91 % for benzo[a]pyrene, by 97–98 % for O3 and, strikingly, by 36–37 % for SO2. Estimates of the health impacts of polluted air show that long-term exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) caused around 432,000 premature deaths in 2012, long-term exposure to NO2 caused around 75,000 premature deaths and short-term exposure of Europeans to O3 caused approximately 17,000 premature deaths (EEA 2015).

Inhabitants of Central and Eastern Europe, including the Balkans, are the most exposed to limit-exceeding concentrations of suspended particles and benzo[a]pyrene. The Po Valley in northern Italy is also among the most polluted areas (Figs. VIII.2 and VIII.3). Ambient limit concentrations of NO2 are exceeded especially in places affected by transport (VIII.4). Above-the-limit concentrations presumably also occur in countries that monitor these pollutants only at a limited number of localities or not at all, as well as in those that do not provide these data to the EEA. Primary pollutants, originating from local and regional sources of emissions, are accompanied by pollution of the air by secondary aerosols (see Chapter IV.1.4) and ozone. Concentrations of ozone, due to the mechanism of its origin (see Chapter IV.4.3), range from low values in Northern Europe to the highest concentrations especially in countries around the Mediterranean Sea (Fig. VIII.5).

The level of air pollution varies strongly in different parts of the Czech Republic. On the one hand, there are some very slightly polluted areas with similar air quality as clean continuously inhabited regions of Europe where concentrations of pollutants far from exceed their limit values. Background concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 measured in the Czech Republic are nevertheless comparable to concentrations in many European cities. In other words, background concentrations in the Czech Republic are higher than at comparable European background localities. On the other hand, the O/K/F-M agglomeration, together with the adjacent part of Poland, is among the most polluted regions of Europe, both in the size of the area affected and the concentrations reached (see Chapter IV.).

Transport of pollutants between the Czech Republic and neighbouring countries is most intensive in the region of Silesia (for details, see Chapter V.3 and Blažek et al. 2013). Polluted air, of course, travels across the state border also in other regions, but mutual cross-border effects are much smaller, and their quantification or estimated influence is usually unavailable. Besides the region of Silesia, the contributions of different sources to the level of air pollution are described in more detail only for the Czech-Slovak border region of the Moravia- Silesian and Žilina regions (VŠB-TU Ostrava 2014). Long-distance transport of pollutants across the continent and beyond it is dealt with by the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (Convention LRTAP) within the framework of the European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme (EMEP 2016a). The programme was founded in 1977. One of its main goals is to monitor long-term trends in air quality on a regional scale, based on measurements at selected background localities. A summary report evaluating the trends of basic pollutants in the context of the CLRTAP convention 1990 (EMEP 2016b) is currently being prepared.

Fig. VIII.1 Development of concentrations of PM10, O3 and NO2 recalculated according to the number of urban inhabitants in 28

member states of the European Union, 2004–2013

Fig. VIII.2 Annual average concentration of PM2.5 in Europe, 2013

Fig. VIII.3 Annual average concentration of benzo[a]pyrene in Europe, 2013

Fig. VIII.4 Annual average concentration of NO2 in Europe, 2013

Fig. VIII.5 The 26th highest maximum daily 8-hour average of O3 concentration in Europe, 2013